RESTful API Design. Best Practices in a Nutshell.

Posted on Mar 4, 2015. Updated on Jun 12, 2022

Designing HTTP and RESTful APIs can be tricky as there is no official and enforced standard. Basically, there are many ways of implementing an API but some of them have proven in practice and are widley adopted. This post covers best practices for building HTTP and RESTful APIs. We’ll talk about URL structure, HTTP methods, creating and updating resources, designing relationships, payload formats, pagination, versioning and many more.

Update 2018

I completely reworked this post. I revisited and extended existing sections and added many new ones: New overviews over HTTP methods and status codes, PATCH, clearify semantics of PUT and POST, data field, designing relationships, REST vs RPC-style APIs, evolvability, versioning approaches, keyset-based pagination, JSON:API, JSON:API-inspired payload formats.

Use Two URLs per Resource

One URL for the collection and one for a single resource:

# URL that represents a collection of resources

/employees

# URL that represents a single resource

/employees/56

Use Consistently Plural Nouns

Prefer

/employees

/employees/21

over

/employee

/employee/21

Indeed, it’s a matter of taste, but the plural form is more common. Moreover, it’s more intuitive, especially when using GET on the collection URL (GET /employee returning multiple employees). But most important: avoid mixing plural and singular nouns, which is confusing and error-prone.

Use Nouns instead of Verbs for Resources

This will keep you API simple and the number of URLs low. Don’t do this:

/getAllEmployees

/getAllExternalEmployees

/createEmployee

/updateEmployee

Instead, express the required action with the available HTTP methods on a small set of URLs. See next section.

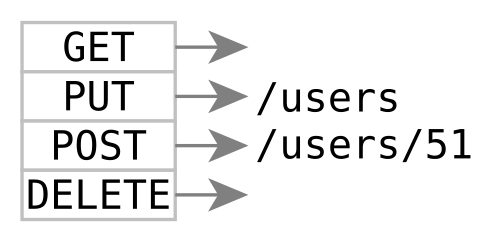

HTTP Methods

Use HTTP Methods to Operate on your Resources

GET /employees

GET /employees?state=external

POST /employees

PUT /employees/56

Use URLs to specify the resources you want to work with. Use the HTTP methods to specify what to do with this resource. With the five HTTP methods GET, POST, PUT, PATCH and DELETE you can provide CRUD functionality (Create, Read, Update, Delete) and beyond.

- Read: Use GET for reading resources.

- Create: Use POST or PUT for creating new resources.

- Update: Use PUT and PATCH for updating existing resources.

- Delete: Use DELETE for deleting existing resources.

Understand the Semantics of the HTTP Methods

Definition of Idempotence: A HTTP methods is idempotent when we can safely execute the request over and over again and all requests lead to the same state.

- GET

- Idempotent

- Read-only. GET never changes the state of the resource on the server-side. It must not have side-effects.

- Hence, the response can be cached safely.

- Examples:

GET /employees- Lists all employeesGET /employees/1- Shows the details of the employee 1

- PUT

- Idempotent!

- Can be used for both creating and updating

- Commonly used for updating (full updates).

- Example:

PUT /employees/1- updates employee 1 (uncommon: creates employee 1)

- Example:

- To use PUT for creating, the client needs to know the whole URL (including the ID) upfront. That’s uncommon as the server usually generates the ID. So PUT for creating is typically used when there is only one element and the URL is unambiguous.

- Example:

PUT /employees/1/avatar- creates or updates the avatar of employee 1. There is only one avatar for each employee.

- Example:

- Always include the whole payload in the request. It’s all or nothing. PUT is not meant to be used for partial updates (see PATCH).

- POST

- Not idempotent!

- Used for creating

- Example:

POST /employeescreates a new employee. The new URL is delivered back to the client in theLocationHeader (e.g.Location: /employees/12). Multiple POST requests on/employeeslead to many new different employees (that’s why POST is not idempotent).

- PATCH

- Idempotent

- Used for partial updates.

- Example:

PATCH /employees/1- updates employee 1 with the fields contained in the payload. The other fields of employee 1 are not changed.

- DELETE

- Idempotent

- Used for deletion.

- Example:

DELETE /employees/1

POST on the Resource Collection URL to Create a New Resource

How could a client-server interaction for creating a new resource look like?

Use POST for creating a new resource

- The client sends a POST request to the resource collection URL

/employees. The HTTP body contains the attributes of the new resource “Paul”. - The RESTful web service generates an ID for the new employee, creates the employee in its internal model and sends a response to the client. This response contains the status code 201 (Created) and a

LocationHTTP header that indicates the URL under which the created resource is accessible.

PUT on the Single Resource URL for Updating a Resource

Use PUT for updating an existing resource.

- The client sends a PUT request to the single resource URL

/employee/21. The HTTP body of the PUT request contains all fields of the employee and every field will be updated on the server-side. - The REST service updates the

nameandstatusof the employee with the ID 21 and confirms the changes with the HTTP status code 200.

Use PATCH for Partial Updates of a Resource

PUT is NOT supposed for partial updates. PUT should only be used for complete replacements of a resource. Sending all fields every time (although you only want to update a single field) can lead to accidentally overwrites in case of parallel updates. Moreover, the implementation of validation is hard as you have to support both use cases: creating (some fields must not be null) and updating (null values to mark fields that should not be updated) at the same time. So don’t use PUT and send only the fields that should be updated. Missing fields in PUT request should be treated as null values and empty the database fields or trigger validation errors.

Instead, use PATCH for partial updates. Send only the fields that should be updated. This way, the request payload is pretty straight-forward, parallel updates of different fields don’t override unrelated fields, validation becomes easier, the semantic of null values is unambiguous (for both PUT and PATCH) and you save bandwidth.

For instance, the following PATCH request updates only the status field but not the name.

Use PATCH and send only the fields you like to update.

Implementation sidenote: Besides the described “just send what you like to update” approach (which is also recommended by JSON:API), there is JSON-PATCH. It’s a payload format for PATCH requests and describes a sequence of changes that should be performed on the resource. However, it’s tricky to implement and overkill for many use cases. For more details, check out the post “PUT vs PATCH vs JSON-PATCH”.

Wrap the Actual Data in a data Field

GET /employees returns a list of objects in the data field:

{

"data": [

{ "id": 1, "name": "Larry" }

, { "id": 2, "name": "Peter" }

]

}

GET /employees/1 returns a single object in the data field:

{

"data": {

"id": 1,

"name": "Larry"

}

}

The payload of PUT, POST and PATCH requests should also contain the data field with the actual object.

Advantages:

- There is space left to add metadata (e.g. for pagination, links, deprecation warnings, error messages)

- Consistency

- Compatible with the JSON:API Standard

Use the Query String (?) for Optional and Complex Parameters

Don’t do this:

GET /employees

GET /externalEmployees

GET /internalEmployees

GET /internalAndSeniorEmployees

Keep your URLs simple and the URL set small. Choose one base URL for your resource and stick to it. Move complexity or optional parameters to the query string.

GET /employees?state=internal&title=senior

GET /employees?id=1,2

The JSON:API way of filtering is:

GET /employees?filter[state]=internal&filter[title]=senior

GET /employees?filter[id]=1,2

Use HTTP Status Codes

The RESTful Web Service should respond to a client’s request with a suitable HTTP status response code.

2xx– success – everything worked fine.4xx– client error – if the client did something wrong (e.g. the client sends an invalid request or he is not authorized)5xx– server error – failures on the server-side (errors while trying to process the request like database failures, dependend services are not available, programming errors or states that should not occur)

Consider the available HTTP status codes. However, be aware, that using all of them could be confusing for the users of your API. Keep the set of used HTTP status codes small. It’s common to use the following codes:

- 2xx: Success

- 200 OK

- 201 Created

- 3xx: Redirect

- 301 Moved Permanently

- 304 Not Modified

- 4xx: Client Error

- 400 Bad Request

- 401 Unauthorized

- 403 Forbidden

- 404 Not Found

- 410 Gone

- 5xx: Server Error

- 500 Internal Server Error

Don’t overuse 404. Try to be more precise. If the resource is available, but the user is not allowed to view it, return a 403 Forbidden. If the resource existed once but now has been deleted or deactivated, use 410 Gone.

Provide Useful Error Messages

Additionally to an appropriate status code, you should provide a useful and verbose description of the error in the body of your HTTP response. Here’s an example.

Request:

GET /employees?state=super

Response:

// 400 Bad Request

{

"errors": [

{

"status": 400,

"detail": "Invalid state. Valid values are 'internal' or 'external'",

"code": 352,

"links": {

"about": "http://www.domain.com/rest/errorcode/352"

}

}

]

}

The proposed error payload structure is inspired by the JSON:API standard.

Provide Links for Navigating through your API (HATEOAS)

Ideally, you don’t let your clients construct URLs for using your REST API. Let’s consider an example.

A client wants to access the salary statements of an employee. Therefore, he has to know that he can access the salary statements by appending the query parameter salaryStatements to the employee URL (e.g. /employees/21/salaryStatements). This string concatenation is error-prone, fragile and hard to maintain. If you change the way to access the salary statement in your REST API (e.g. using now “salary-statements” or “paySlips”) all clients will break.

It’s better to provide links in your response which the client can follow. For instance, a response to GET /employees may look like this:

{

"data": [

{

"id":1,

"name":"Paul",

"links": [

{

"salary": "http://www.domain.com/employees/1/salaryStatements"

}

]

}

]

}

If the client exclusively relies on the links to get the salary statement, he won’t break if you change your API, since the client will always get a valid URL (as long as you update the link in case of URL changes). Another benefit is that your API becomes more self-descriptive and the clients don’t have to look up the documentation that often.

Design Relationships Appropriately

Let’s assume that each employee has a manager and several teamMembers. There are basically three common options to design relationships within an API: Links, Sideloading and Embedding.

They are all valid and the right choice depends on the use case. Basically, you should design the relationships depending on the client’s access schema and the tolerable request amount and payload size.

Links

{

"data": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Larry",

"relationships": {

"manager": "http://www.domain.com/employees/1/manager",

"teamMembers": [

"http://www.domain.com/employees/12",

"http://www.domain.com/employees/13"

]

//or "teamMembers": "http://www.domain.com/employees/1/teamMembers"

}

}

]

}

- Small payload size. It’s good, if the client doesn’t need the

managerand theteamManagerevery time. - Many Requests. It’s bad, if nearly every client needs this data. Many additional requests may be required; in the worse case for every employee. And this is multiplied by every relationship (

manager,teamMembersand so on) an employee has. - The client has to stitch the data together in order to get the big picture.

Sideloading

We can refer to the relationship with a foreign key and put the referred entities also in the payload but under the dedicated field included. This approach also called “Compound Documents”.

{

"data": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Larry",

"relationships": {

"manager": 5 ,

"teamMembers": [ 12, 13 ]

}

}

],

"included": {

"manager": {

"id": 5,

"name": "Kevin"

},

"teamMembers": [

{ "id": 12, "name": "Albert" }

, { "id": 13, "name": "Tom" }

]

}

}

The client may also control the sideloaded entities by a query parameter like GET /employees?include=manager,teamMembers.

- We get along with a single request.

- Tailored payload size. No duplication (e.g. you only deliver a manager once even if he is referenced by many employees)

- The client still has to stitch the data together in order to resolve the relationships, which can be very cumbersome.

Embedding

{

"data": [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Larry",

"manager": {

"id": 5,

"name": "Kevin"

},

"teamMembers": [

{ "id": 12, "name": "Albert" }

, { "id": 13, "name": "Tom" }

]

}

]

}

- Most convenient for the client. Is can directly follow the relationships to get the actual data.

- Relationships may be loaded in vain if the client doesn’t need it.

- Increased payload size and duplications. Referenced entities may be embedded multiple times.

Use CamelCase for Attribute Names

Use CamelCase for your attributes identifiers.

{ "yearOfBirth": 1982 }

Don’t use underscores (year_of_birth) or capitalize (YearOfBirth). Often your RESTful web service will be consumed by a client written in JavaScript. Typically the client will convert the JSON response to a JavaScript object (by calling var person = JSON.parse(response) ) and call its attributes. Therefore, it’s a good idea to stick to the JavaScript convention which makes the JavaScript code more readable and intuitive.

// Don't

person.year_of_birth // violates JavaScript convention

person.YearOfBirth // suggests constructor method

// Do

person.yearOfBirth

Use Verbs for Operations

Sometimes a response to an API call doesn’t involve resources (like calculate, translate or convert). Example:

//Reading

GET /translate?from=de_DE&to=en_US&text=Hallo

GET /calculate?para2=23¶2=432

//Trigger an operation that changes the server-side state

POST /restartServer

//no body

POST /banUserFromChannel

{ "user": "123", "channel": "serious-chat-channel" }

In this case, no resources are involved. Instead, the server executes an operation and returns the result to the client. Hence, you should use verbs instead of nouns in your URL to distinguish clearly the operations (RPC-style API) from the REST endpoints (resources for modelling the domain).

Creating those RPC-style APIs instead of REST APIs is appropriate for operations. Usually, it’s simpler and more intuitive than trying to be RESTful for operations (like PATCH /server with {"restart": true}). As a rule of thumb, REST is nice for interacting with domain models and RPC is suitable for operations. For more details, check out “Understanding RPC Vs REST For HTTP APIs”.

Provide Pagination

It is almost never a good idea to return all resources of your database at once. Consequently, you should provide a pagination mechanism. Two popular approaches are:

- Offset-based Pagination

- Keyset-based Pagination aka Continuation Token aka Cursor (recommended)

Offset-based Pagination

A really simple approach is to use the parameters offset and limit, which are well-known from databases.

/employees?offset=30&limit=15 # returns the employees 30 to 45

If the client omits the parameter you should use defaults (like offset=0 and limit=100). Never return all resources. If the retrieval is more expensive you should decrease the limit.

/employees # returns the employees 0 to 100

You can provide links for getting the next or previous page. Just construct URLs with the appropriate offset and limit.

GET /employees?offset=20&limit=10

{

"pagination": {

"offset": 20,

"limit": 10,

"total": 3465,

},

"data": [

//...

],

"links": {

"next": "http://www.domain.com/employees?offset=30&limit=10",

"prev": "http://www.domain.com/employees?offset=10&limit=10"

}

}

Keyset-based Pagination (aka Continuation Token, Cursor)

The presented offset-based pagination is easy to implement but comes with severe drawbacks. They are slow (SQL’s OFFSET clause becomes very slow for large numbers) and unsafe (it’s easy to miss elements when changes are happening during pagination).

That’s why it’s better to use an indexed column. Let’s assume that our employees have an indexed column data_created and the collection resource /employees?pageSize=100 returns the oldest 100 employees sorted by this column. Now, the client only has to take the dateCreated timestamp of the last employee and uses the query parameter createdSince to continue at this point.

GET /employees?pageSize=100

# The client receives the oldest 100 employees sorted by `data_created`

# The last employee of the page has the `dataCreated` field with 1504224000000 (= Sep 1, 2017 12:00:00 AM)

GET /employees?pageSize=100&createdSince=1504224000000

# The client receives the next 100 employees since 1504224000000.

# The last employee of the page was created on 1506816000000. And so on.

This solves already many of the disadvantages of offset-based pagination, but it’s still not perfect and not very convenient for the client.

- It’s better to create a so-called continuation token by adding additional information (like the id) to the date in order to improve the reliability and efficiency.

- Moreover, you should provide a dedicated field in the payload for that token so the client doesn’t have to figure it out by looking at the elements. You can even go further and provide a

nextlink.

So GET /employees?pageSize=100 returns:

{

"pagination": {

"continuationToken": "1504224000000_10",

},

"data": [

// ...

// last element:

{ "id": 10, "dateCreated": 1504224000000 }

],

"links": {

"next": "http://www.domain.com/employees?pageSize=100&continue=1504224000000_10"

}

}

The next link makes the API really RESTful as the client can page through the collection simply by following these links (HATEOAS). No need to construct URLs manually. Moreover, you can simply change the URL structure without breaking clients (evolvability).

For more details, check out the dedicated posts about Web API pagination:

- Web API Pagination with the ‘Timestamp_Offset_Checksum’ Continuation Token - The proposed approach is not recommended any more, but the post introduces nicely into the whole topic (including offset-based pagination).

- Web API Pagination with the ‘Timestamp_ID’ Continuation Token - I recommend to use this approach. It also contains an overview of existing keyset-based pagination approaches.

Check out JSON:API

You should at least take a look at JSON:API. It’s a standard format for the JSON payload and the resources of an HTTP service (MIME type: application/vnd.api+json). I personally don’t follow all recommendations since some of them feel a little bit over-formalized and overkill for me. To my mind, the achieved flexibility is often not required, but it complicates the implementation without providing a benefit. But it’s a matter of taste and following standards is basically a good idea. I use it as an inspiration and pick those elements that make sense for me. Feel free to make up your own mind about JSON:API.

Ensure Evolvability of the API

Avoid Breaking Changes

Ideally, REST APIs (as every API) should be stable. Basically, breaking changes (like changing the whole payload format or the URL scheme) should not happen. But how can we still evolve our API without breaking the clients?

- Make backward-compatible changes. Adding fields is no problem (as long as the clients are tolerant).

- Duplication and Deprecation. In order to change an existing field (rename or change structure), you can add the new one next to the old field and deprecated the old one in the documentation. After a while, you can remove the old field.

- Utilize Hypermedia and HATEOAS. As long as the API client uses the links in the response to navigate through the API (and doesn’t craft the URLs manually), you can safely change the URLs without breaking the clients.

- Create new resources with new names. If new business requirements lead to a completely new domain model and workflows, you can create new resources. That’s often quite intuitive as the domain model has a new name anyway (derived from the business name). Example: A rental service now also rents bikes and segways. So the old concept

carwith the resource/carsdoesn’t cut it anymore. A new domain modelvehiclewith a new resource/vehiclesis introduced. It’s provided along with the old/carsresource.

Keep Business Logic on the Server-Side

Don’t let your service become a dump data access layer which provides CRUD functionality by directly exposing your database model (low-level API). This creates high coupling.

- The business logic is shifted to the client and is often replicated between the client and the server (just think about validation). We have to keep both in sync.

- Often, the client is coupled to the server’s database model.

We should avoid creating dump data access APIs because they lead to high coupling between the server and the clients because the business workflows are getting distributed between the client and the server. That, in turn, makes it likely that new business requirements require a change in both the client and the server and to break the API. So the API/system is not that evolvable.

So we should build high-level/workflow-based APIs instead of low-level APIs. An example: Don’t provide a simple CRUD service for the order entities in the database. Don’t require the clients to know that to cancel an order, the client has to PUT an order to the generic /order/1 resource with a certain cancelation payload (reflecting the database model) in it. This leads to high coupling (business logic and domain knowledge on the client-side; exposed database model). Instead, provide a dedicated resource /order/1/cancelation and add a link to it in the payload of the order resource. The client can navigate to the cancelation URL and send a tailored cancelation payload. The business logic for mapping this payload to the database model is done in the server. Moreover, the server can easily change the URL without breaking the client, because the client simply follows links. Besides, the decision logic, if an order can be canceled or not is now in the server: If a cancelation a possible the server adds the link to the cancelation resource in the order payload. So the client only has to check if the cancelation links are present (for example to know if he should draw the cancelation button). So we moved domain knowledge away from the client back to the server. Changes to the cancelation conditions can be easily applied by only touching the server, which in turn make the system evolvable. No API change is required.

If you like to read more about this topic, I recommend the talk REST beyond the obvious – API design for ever evolving systems by Oliver Gierke.

Consider API Versioning

Nevertheless, you might end up in situations where the above approaches don’t work and you really have to provide different versions of your API. Versioning allows you to release incompatible and breaking changes of your API under a new version without breaking the clients. They can continue consuming the old version. The clients can migrate to the new version at their own speed.

This topic is hotly disputed in the community. You should take into account that you may end up building and maintaining (!) different versions of an API for a long time, which is expensive.

If you are building internal APIs you most likely know all of your clients. So performing breaking changes can be an option again. But it will require more communication and a coordinated deployment.

Nevertheless, here are the two most popular approaches for versioning:

- Versioning via URLs:

/v1/ - Versioning via the

AcceptHTTP Header:Accept: application/vnd.myapi.v1+json(Content Negotiation)

Versioning via URLs

Just put the version number of your API in the URL of every resource.

/v1/employees

Pros:

- Extremely simple for API developers.

- Extremely simple for API clients.

- URLs can be copied and pasted.

Cons:

- Not RESTful.

- Breaking URLs. Clients have to maintain and update the URLs.

Strictly speaking, this approach is not RESTful because URLs should never change. This prevents easy evolvability. Putting the version in the URL will break the API some day and your clients have to fix the URLs. The question is, how much effort would it take the clients to update the URLs? If the answer is “only a little” then URL versioning might be fine.

Due to its simplicity, URL versioning is very popular and widely used by companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google/YouTube, Bing, Dropbox, Tumblr, and Disqus.

Versioning via Accept HTTP Header (Content Negotiation)

The more RESTful way for versioning is to utilize content negotiation via the Accept HTTP request header.

GET /employees

Accept: application/vnd.myapi.v2+json

In this case, the client requests the version 2 of the /employees resource. So we treat the different API versions as different representations of the /employees resource, which is pretty RESTful. You can make the v2 optional and default to the latest version when the client only requests with Accept: application/vnd.myapi+json. But be fair and give him a warning that his app may break in the future if he doesn’t pin the version.

Pros:

- URLs keep the same

- Considered as RESTFul

- HATEOAS-friendly

Cons:

- Slightly more difficult to use. Clients have to pay attention to the headers.

- URLs can’t be copied and pasted anymore.

Personal Thoughts about Versioning

When creating a new API, try it without URL versioning. Especially internal APIs might never need a real version 2 for the existing resources at all. You might get along with the approaches describted in the section “Avoid Breaking Changes” . If you finally really need a new version for an existing resource, you can still go for content negotiation and utilize the Accept header. But in general it’s better to build an API that makes breaking changes less likely in the first place (e.g. by building a high-level/process flow API and keep business logic in the server).

There are endless discussions about the right way to version an API and what is RESTful and what not. People are getting really upset. I prefer to be pragmatic. For me, it’s totally fine if you don’t care about the REST theory when it comes to versioning (and use URL versioning) as long it works for you, your clients and you are aware of the upcoming maintenance costs. “Protip”: Speak about “Web API” or “HTTP API” instead of “REST API” to be honest about the conformity with REST and to calm the REST zealots. ;-)

Further Readings

- I highly recommend the book Build APIs You Won't Hate

by Phil Sturgeon

- I wrote a post about Best Practices for Testing RESTful Services in Java.

- JSON:API Standard

- A Response to REST is the new SOAP (REST confusion explained) by Phil Sturgeon

- Understanding RPC Vs REST For HTTP APIs by Phil Sturgeon